Skillful Effort

Episode 216 of the Secular Buddhism Podcast

Welcome back to another episode of the Secular Buddhism Podcast. I am your host, Noah Rasheta, and today I'm sharing the audio of a live Dharma talk I gave. This is part six of an eight-part series covering the topic of the Eightfold Path. Part six is about wise or skillful effort, also known as right effort. So without further ado, this is the audio of that live Dharma talk.

Where We Are on the Path

Over the last several weeks, we've been going over each of the aspects of the Eightfold Path. The Eightfold Path, I like to think of it kind of like a practical map or an outline for living more skillfully. It's at the heart of what you could consider the Buddhist practice, and over the past several weeks we've been exploring the various aspects of the path.

We started with the territory of the path that we would call wisdom, and that entails skillful view and skillful intention. That's kind of like getting the map itself. You have a map now that gives you a better understanding of where you are, where you're trying to go. The map helps you to see clearly: what is it that leads to suffering, and what is it that leads to greater inner peace? So that's the wisdom portion of the path.

Then we talked about ethical conduct, which entails skillful speech, skillful action, and skillful livelihood, which is what we talked about last week. If wisdom is the map, then our ethics and our conduct are kind of like the vehicle that we're building to travel on this path. The vehicle that allows us to move through the world more compassionately, with more integrity.

And then we get to the portion of the path that is like the final territory of the map: mental discipline. This is really where the rubber meets the road, in a way, because you have the map, you have the vehicle that you're building to navigate on this map, but now you need to pay attention to who is driving the vehicle. You want someone who's awake and focused and knows how to operate the controls. That's kind of what mental discipline is. It's like training the driver of the vehicle to navigate the terrain.

And the very first control that we start to learn to use is the accelerator and the brake in the vehicle: the application of energy. So that's where we are today, the topic of skillful effort.

The Problem with "Try Harder"

I'm sure we can all think of a time when we've probably worked really hard or tried really hard to achieve something and, after all that effort, realized we didn't really achieve what we wanted. Maybe we got nowhere in the process. Maybe it was a project that you were working on. Maybe it was an argument you had with a loved one where it felt like the more you try to fix it, the worse it gets. At times we feel like we're just pushing this really heavy boulder up a hill and we're not making any progress because the boulder's too heavy and we don't have the strength to push it uphill.

Or you could probably think of a time in your life when you felt like you should be doing something. Maybe it was starting to exercise, or starting a difficult task because you have a whole big project and it all starts with that first step. Or maybe it's meditation, starting the practice of meditation. Whatever it was, you felt like you just couldn't muster the energy to do it. You felt stuck, maybe depleted or without energy, or maybe just felt like "I don't have the skills or ability to even attempt this, so I'm not going to try."

So that's kind of where effort comes in. And the tricky thing with effort is that we live in a culture and a society that typically gives us only one instruction when it comes to effort, and that is: more. Hustle harder. Grind harder. Never give up. It's like the lyrics of that song, "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger." This approach really treats all problems as if they're a nail and all you have to do is use the sledgehammer. Hit it more, hit it harder.

But the result from that is, well, first, not everything is a nail. The hammer's not the right tool for everything. And second, we either burn out or we feel like failures when we just try harder but still don't achieve the thing that we're trying to achieve.

This is why skillful effort is so important, because it's not about more effort. It's about wise effort or skillful effort, which could mean doing less.

The Gardener Analogy

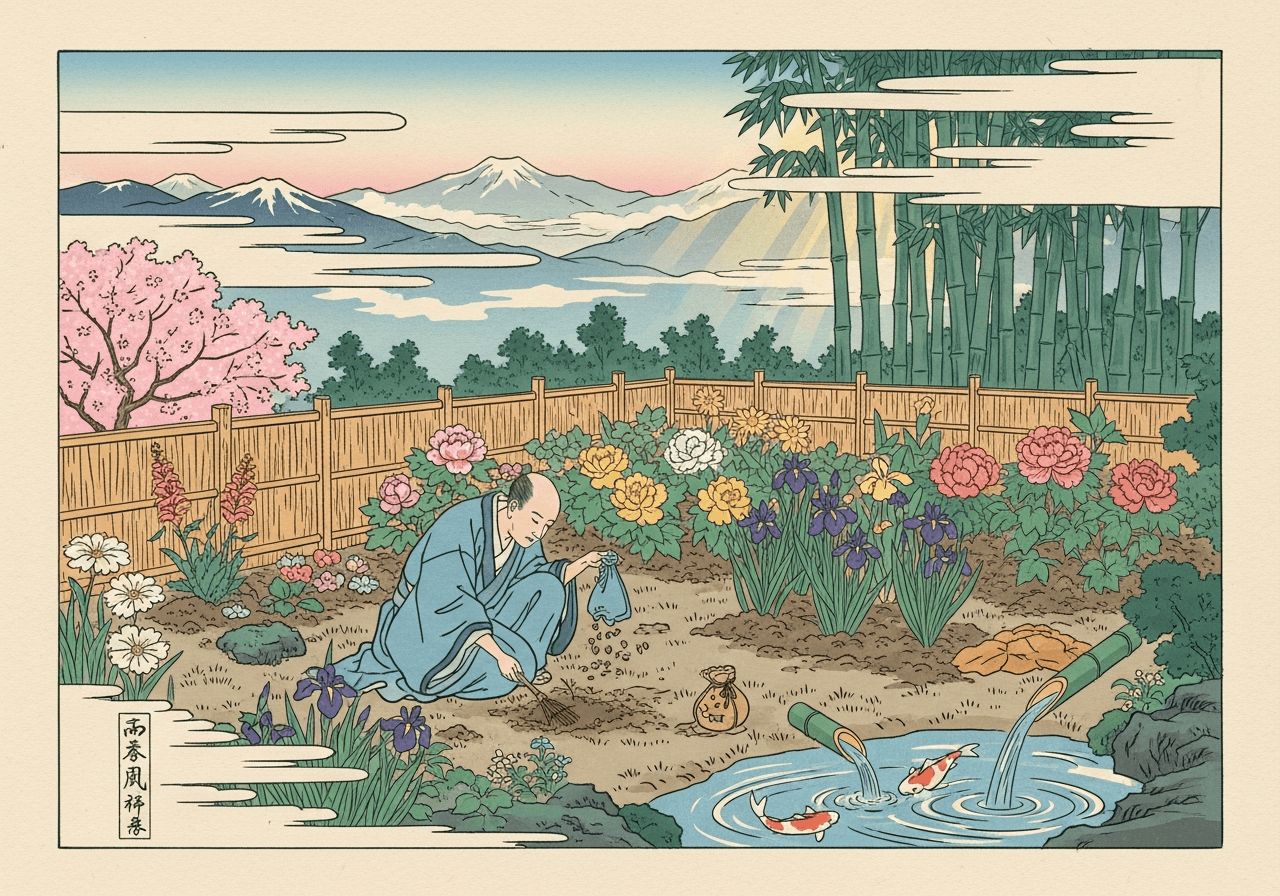

It's about learning to be a gardener. I like this analogy of thinking of it as approaching life like a garden, or approaching the mind like a garden. It's about knowing when to do things and when not to do things. When do you plant? When do you weed? When do you just sit back and let the rain and the sun do their work?

What I hope you'll gain from today's discussion on skillful effort is not just a tool to be more productive. It's not about that. It's a way to be more sustainable with how you engage with life, with your work, with your own mind, in a way that feels like genuine organic growth rather than just the hustle of always trying.

So how do we do this? How do we become skillful gardeners of our own mind?

The Four Tasks of Skillful Effort

In traditional Buddhist teachings on skillful effort, the teaching breaks it down into four simple, elegant instructions. You could think of these as four tasks.

The first one is: prevent the unskillful from arising in your mind. The second one is: abandon the unskillful that has already arisen in your mind. The third is: cultivate the skillful things that have not yet arisen in your mind. And the fourth is: maintain the skillful that has already arisen in your mind.

So we can just think of it as preventing, abandoning, cultivating, and maintaining.

And if you think, "Well, what does that mean? What is unskillful?" I like to think of the unskillful as the thoughts, emotions, propensities, and habits that lead to more stress or more harm or more suffering for myself and others. That's it. As an example, this could be an unskillful relationship with your anger, or an unskillful relationship with the anxiety that you experience. It could just be mindless distraction.

The flip side of it, the skillful side, is the opposite. These are the states, the propensities, the actions, the habits that lead to greater clarity and understanding, or lead to greater peace and greater well-being, greater compassion, greater kindness for ourselves and for others.

The Garden of the Mind

If we take this and reimagine it in our analogy of the garden, specifically the garden of the mind:

Preventing is like building a fence around your garden. This keeps deer out, or rabbits, or whatever the pest might be that's affecting your garden.

Abandoning is the process of weeding. When weeds pop up (because they do, right? The nature of a garden is that things grow in it and you're trying to determine what you want to keep and what you want to get rid of), you gently but firmly remove them before they take over.

Cultivating is the action of actually planting what you want in the garden. You intentionally decide: am I planting flowers? Am I planting vegetables? Am I planting fruit? What is it that I want in my garden?

And I will say on a side note here, this correlates with another aspect of the path: wise view, or skillful view, or understanding. You need to know that, hey, maybe the reason the coconut tree isn't growing is because coconut trees don't grow where you live. Maybe you should be planting cucumbers or strawberries or whatever can actually grow in the climate where you live.

Maintaining is the effort or work that goes into care: watering, making sure the plants are getting sun, making sure they're taken care of, along with all the other three aspects of caring for that garden.

And what you'll notice here is balance. Gardening doesn't mean you just go out and weed and that's it. Building a fence? No, that's not it either. Just watering all day? No, that's not it, right? It's the balance of the whole process. Sometimes you do this, sometimes you do that. But you recognize that it's an ongoing, dynamic process. And that's how this four-part framework should work. This is the "how" of applying energy wisely to the process of gardening.

Practical Examples

So to make this more practical, we could look through each of these four aspects of effort with examples from ordinary day-to-day life.

Building the Fence

For me, an example of the fence would be: let's say I know that scrolling through social media first thing in the morning might make me feel anxious and uneasy for the day. Skillful effort here isn't to fight that anxiety and say, "Just will yourself to not be anxious when you do it." No. It's saying, "I'm going to prevent it." So maybe I don't check social media first thing when I wake up. Or maybe it means I don't sleep with my phone in my room. Maybe I put it in another room and charge it there overnight so that I can actually wind down and sleep. Maybe when I first wake up, I'm going to have a routine: five minutes of meditation or stretching, or look out the window and see what's going on in the world before I just check the news. You're building a fence around the peace of your morning.

Or it could be in relationships. It could be at work. There's always this one coworker that just likes to push my buttons, and I know that if I go into that meeting, that daily meeting, it's going to trigger this response mechanism in me where they're going to say their thing and I always have to reply. Well, maybe I'll decide my fence is: I don't have to reply. Let the person say what they're going to say and I just don't have to say anything back. And that's how I'm protecting my inner peace.

Pulling the Weeds

With the analogy of the garden and pulling the weeds, this is an active component of effort because we know weeds grow everywhere. They're going to grow in the garden. That's a given. The question is, what do you do when you notice, "Oh, there's a weed. I don't want that weed in here."

And I'll add a side note here: you don't weed the garden and when you're done think, "That's it. I did it. I weeded the garden and now I don't have to worry about it." Because what's going to happen tomorrow or a week from now? More weeds. It's an ongoing process. It's cyclical in nature.

Here's an example of this in day-to-day life. You're driving, you get cut off in traffic. I use this one a lot. The event is usually over in one or two seconds. But then for the next 10 minutes, you're replaying it in your mind, thinking, "This jerk cut me off. This person could have killed me." Now that chain of thought is the initial weed. You're feeding it and watering it and giving it attention and watching it grow.

The effort to abandon in this sense is just to notice it, let it be what it is, acknowledge it: "Ah, anger, there you are. You popped in there quick after I got cut off." And that's it. You don't have to try to suppress it or try to yell at it. You just see it for what it is. It's just a weed in my mental garden. Then you withdraw your attention and bring your focus back to what you're trying to do: the steering wheel, or the music you're listening to on the radio. Listen to the lyrics, something like that.

Rather than thinking, "Here's this weed, here's this thought. I have to pull it out." I'm not sure the analogy of pulling weeds is even helpful in this sense, because that's not how the mind works. You don't have a thought and just will yourself to not have the thought. So maybe it's more appropriate to think of it as: where am I putting my energy and my attention?

This is where the teaching of the second arrow, I think, correlates well. You can't always avoid the first arrow, the event, like being cut off. But skillful effort is not intentionally shooting ourselves with that second arrow, still thinking about it ten minutes later.

Planting the Seeds

The third part of the gardening process, cultivating, ties in here as well. This is where we recognize we are active creators in our inner landscape. It takes effort to plant the garden that we want. You have to think about what you want to plant. You have to go to the store, buy the seeds, buy the tools you're going to use for your garden. And then there's the actual digging a hole and putting the seed in that hole. It's that whole process of planting.

I like to think of that story I'm sure you've all heard before: the analogy of the two wolves. Which one is going to win? The one that you feed. That's kind of the idea here with cultivating. In our mind, there are weeds and there are flowers. All of them are there, but what are you going to feed? What are you going to focus on?

As a practical example, maybe you notice that your mind has a default tendency towards the negative or towards pessimism. Not that there's anything wrong with that. You just notice that's your natural tendency or your habit energy. So now the skillful effort here of cultivation is to say, "Well then, I need to put more effort into intentionally planting seeds of gratitude." So I might take up the habit every night to journal before going to bed and write down three things that went well for me today, or three things that I'm grateful for. For you, that practice might be more skillful because you're trying to cultivate a new tendency or a new propensity to balance the other tendency. Does that make sense? Rather than thinking of it as, "I need to not be the way that I am." No, that's not going to help. That actually makes it worse.

So that's the idea with planting gratitude. With consistent and gentle effort, the seed will sprout and then you begin to genuinely notice more things that you're grateful for, because that's what you've been practicing.

Another example here: maybe it's not natural or easy for you to be kind. Okay, then I'm going to make a conscious effort to try to offer one genuine compliment per day to a colleague, an acquaintance, or a family member, if maybe that's where you struggle, within your family circle. That becomes your new thing that you're trying to cultivate. Maybe it's when you listen to a friend or someone who's talking to you about their day, you think, "I'm going to listen and not offer advice. I'm just going to offer my presence." Whatever the thing is, each act is a seed of connection and compassion that we're planting in the garden of our minds.

Tending the Garden

So then we have the fourth one: the effort to maintain. This is the overall process of tending the garden. And I think it's important here to recognize two fundamental realities of gardening.

One is knowing it's an ongoing process, like I mentioned before. It's not a one and done. You're not a great gardener because you weeded and now you're done. It's an ongoing thing. A great gardener never finishes the process. They're always working on their garden.

The second is knowing you are the gardener. No one's coming to garden your garden for you. As much as you would love for the neighbor to come and offer help, it's your garden. In your mind, it's you. You are the gardener. And no one's coming to save you.

So when I recognize, "Okay, this is an ongoing process and it's on me. I'm the gardener of my garden," that might be the first and most important step of this teaching on the effort to maintain. It's like, okay, it's on me. So what am I going to do about it?

Finding Balance

Here you can correlate this with the other teachings in Buddhism, like the Middle Way. The Buddha taught using the example of the lute string: if it's tuned too tight, it doesn't sound very good and it could snap. That's like getting burned out, overdoing it. But the opposite's also true. If it's too loose, it's not going to sound very good. Being lazy and complacent might not be the answer either.

So where is that balance? How do I find that balance, knowing that it's up to me, I'm the gardener, but also knowing that doesn't mean I should go out and work in my garden 24/7? Sometimes you don't garden. If it's storming outside, I'm not worrying about the garden today. It's raining. If I'm sick, I'm not gardening today. I'm sick. Or maybe you think, "Well, it's really hot today, so I'll garden tonight." But I don't have a light. Okay, then I won't garden tonight because I don't have a way to see. It implies that you're going to have an understanding of what is the right way for you. You can look at the neighbor and see what's working for them, but that doesn't mean you have to copy them, because your garden is your garden.

And then there's consistency over duration. I talk about this when talking about meditation as a practice. Let's say you've cultivated a habit where you say, "I'm going to meditate every day for fifteen minutes," and you become consistent with it. But one day you're exhausted and overwhelmed. If you have that all-or-nothing mindset that's like, "Well, I can't do 15 minutes, so I guess I'm not going to do anything," and then, "If I didn't meditate today, then I guess I'm just done with this. This isn't for me," that's not helpful.

If you approach it thinking, "I'm not going to do 15 minutes today. Today I can only do five minutes. Or maybe even that's too much. I'm going to do 60 seconds today. That's all I've got in me," that mindset of consistency and habit over duration, I think, is much more effective. And that's how it is with gardening as well. I'm going to try to do a little bit every day rather than in one day build the world's greatest garden. That's just not how it works.

Start Small

So we have this mental model now that we can think of with gardening. We've got the fence, we've got weeds, we've got the plants that we do want, and then we've got the process: watering, making sure the garden gets sun, and all of that.

It might feel like a lot, and you might have the thought that, "Okay, well, I guess this week I've got to go master all of it. I've got to build the fence and dig the trenches and buy the seeds." Don't let it overwhelm you. Pick one thing.

Maybe this week you're just going to study what kind of plants grow in your environment. It could be as simple as that. But think of it like that. A good gardener knows their garden really well. And our goal here in the practice is to become the gardener of our mind. We want to understand ourselves really well, to know: what makes you tick? Why do I say and think and do the things that I do? What are my propensities? How do I react when I'm feeling angry, when I'm feeling hungry, when I'm jealous, or whatever the thing is? And then just observe.

That might actually be the most skillful first part of this entire process. If you haven't been practicing and you're not ready to just go out and start gardening, first read a book about gardening before you go out and start gardening.

I use this analogy with paragliding. I've mentioned it before, where I usually tell students once they come and they learn to fly, they think learning to fly was it. But it's like, no, this is just the very beginning. Because you know what's much more important than learning to fly? Understanding the sky. And everyone's like, "Oh no, that sounds incredibly boring." And it is kind of boring, but I would always tell them: if the sky is going to be your playground and you're going to be spending time now in the sky as a paragliding pilot, you need to understand your playground, the sky.

It's like that, taking that approach of wanting to be more masterful with the inner workings of my own mind. It starts with observing and paying attention and noticing, "Oh, this is what I tend to do when I'm angry," or "This is what I tend to do when..." whatever.

An Invitation

So that would be my invitation to you after today's topic. Over the next week, just pick one area that you want to focus on.

If it's out of those four aspects of gardening, whether it's something to prevent (the fence building), ask: what's one thing I could build to protect my peace a little bit more? Maybe it's the effort of abandoning. What's one thing I'm going to try to let go of? A weed that I'm going to try to eradicate from my garden. Or maybe it's cultivation. What is one thing I want, a new habit I want to bring into this? What is a new seed I want to plant? Or just the overall maintenance. What's a new habit that I can commit to? I'm going to water the garden three times a week or four times a week, whatever it is.

So you get the idea. And this is the path. Remember, the path is a journey. We're not trying to sprint up to the top of a mountain. That's not what mindfulness practice is. You're not pushing a boulder up a hill. It's a patient, wise, deeply rewarding practice of gardening. That's what all of this is.

And the effort that you apply is skillful effort. It's not brute force. You can't will the garden into existence through brute force. But through understanding, through knowledge, through care, through time and attention, a garden can grow. It can be a beautiful garden. And without even realizing it, suddenly you have this really nice garden that you've been working on and cultivated.

So that's the topic that I wanted to share today, specifically skillful effort, around our overall discussion of the Eightfold Path. And now I'd like to open this up to reflections, questions, and just learn from each other's gardening experiences, and use this as a chance to explore how this idea of skillful effort shows up in your lives.