Dying to Live: A Conversation with Andy Chaleff

Episode 215 of the Secular Buddhism Podcast

Host: Noah Rasheta

Guest: Andy Chaleff

Noah Rasheta: Welcome, Andy. You've written a book on a topic that most people spend their entire lives trying to avoid thinking about. Tell me a little bit about that. What was the catalyst for you? What draws a person to dive so deeply into the subject of death?

Andy Chaleff: You know, I've often found that I go to discomfort. That's what I'm drawn to. The vulnerability and discomfort is... it's always been something that I felt was inspiring to me because if I can go to that place, I know others will potentially resonate with it, right? They'll have that sense like, "Wow, I'm not alone in that feeling."

There were so many feelings around death that I had that it was like, "Wow, I can write a book on this." It was almost like, "Why would you want to?" Of course, but then again, there's a lot of content there. Then I spent a good two to three years just hashing that out and realizing that I wanted to spend time in a place where I just wasn't feeling as comfortable and let that guide me.

That was the journey. It was really more of a discovery than a "Let me tell you everything I know about a given subject." It was just very... I enjoy writing that way.

Noah: That's neat. Yeah. I think a lot of people want to avoid it. I think it's neat that you leaned into it rather than running away from it. In chapter two, you talk about that 3 AM panic, that existential dread, and how it feels like a universal human experience. I think at some point, everyone will feel that, maybe. For some, it might be early on, like for you. Others, it might be towards the end or at the very end. Can you talk a little bit about that feeling? Why, instead of running from it, you decided to turn and face it directly?

Andy: It's funny. One of the hardest things about writing is that you have to go back to an experience you had and somewhat relive it and write from the experience again. There are some experiences you don't really want to relive, right? You don't want to sit in what it was and then write from that space. That existential feeling was like that. It was that moment when I just woke up in the middle of the night and my heart was pounding.

Then the words, "eternal nonexistence," the ego death that I wasn't able to even allow myself to come close to in terms of making any peace with it. So that was very raw and real at a very young age. I didn't really discuss it all that much because it was uncomfortable. Even voicing it in public was a bit like... someone mentioned that the film Barbie came out when they were all dancing and then the character says, "Have you guys ever thought about death?" It's like that feeling, right? Why would we be discussing this?

That sense, and I had a lot of that as a kid. A lot of people were like, "Why are we discussing it?" It wasn't something you wanted to bring up.

Noah: Yeah, that's interesting, isn't it? That we don't like to talk about it. I think I was probably around 13 when a good friend of mine from elementary school died of leukemia. I don't remember the specifics. I remember it was very impactful for me, but I remember that, like you said, it's something we're not supposed to talk about.

My most recent encounter with death was when my dad passed away. On my mom's side of the family, my aunts were like, "Really look after your mom. She's going to be sad. She shouldn't be sad. We don't want her to cry. Let's make sure she doesn't cry, call her a lot, and don't talk about your dad." I was like, "Wait a second. That seems totally counterintuitive." But it's almost like a societal taboo.

Andy: Yeah. The best part of writing is it's an iterative process. So, as I was writing, there was that one chapter in the book which was talking to people about writing a book about death and seeing their reaction to it. That was humorous. I saw that people were telling me they loved me more than any other time in my life, spontaneously, because there was this idea like, "Do you have some premonition? Are you sick? Why would you write such a thing?"

So, I even could feel a weird heaviness. I hadn't expected it because all of this energy was being pushed on me. Like, wow, are you seeing something that you don't want to tell? And using the book to share it? It was quite funny.

There's this well-known executive coach who I had lunch with—I'll leave him nameless—and he said to me, "Andy, whatever you write about, you attract into your life." So it was almost like he was saying I was inviting death without saying it directly.

I kept thinking, wow, it's amazing how heavy the subject is held and therefore creates so much constriction. Because if you're around people that are uncomfortable with a subject, you feel it. Then you don't want to discuss it, so I spent two or three years with it.

Noah: Yeah. And it's too bad because it really can be such a transformative thing. Like, you mentioned the people that you have interacted with and that suddenly they're different with you. Have you noticed the same backwards? Like, because it's on your mind a lot as you've been writing it, you tend to be more kind or compassionate to others?

Andy: I've always been that way, which is why I wrote the book. I've always felt like when I say goodbye to someone, it might be the last time I ever see them, and I really hold that very close. There's something that's always made my life, in a way, more special in some ways because these moments are cherished—these simple moments which don't seem to need to have any meaning. I really give them a lot of meaning.

That was part of the reason why I wrote the book. Wow. I hold death so closely that it becomes an impetus for so much more love in my life. I thought, well, it would be nice not just to write that in a nice little meme, but what is the life journey that brings a person to that place? What does life look like when that's what you hold closer than maybe most people are comfortable with?

Noah: Yeah, I love that. I feel like I've experienced the same thing by thinking about it. So, for me, there was that early moment in my childhood with a friend dying, but it wasn't until college that one of my closest friends and business partners got cancer. Then, as he went through that final transition of weakening until the point that he passed away, we were both probably in our upper twenties.

So around just after college, he was still very young, but that became probably the biggest inflection point for me to think about it often. And I noticed it really does change things. While he was sick for the last several months, he recommended a book that he had encountered called The Tibetan Book of the Dead. I read it, and by the time I finished it, he had already passed.

But I remember the number one thing I remember about that whole experience was how unfortunate that we don't think about death often enough. I wanted to think about it every day. And I think since then, I've done what you describe where you... I try to think of it all the time. My parents, my siblings, my kids. It's a very difficult thing to sit through, but it's so impactful because if you think about it often, then it really does make the little things feel big and the big things feel little. Yeah, I think it's a very meaningful way to live, which is what drew me to your book as soon as I saw the title. I was like, "This is what we need to talk about. This stuff." So I was very happy to see that another book on this topic, and the way you framed it all, was really well done.

Andy: Well, yeah, I'm really grateful that you got into it. Yeah, it's... There are stories that I will repeat over and over again because they fill the narrative, but when you repeat them so often, they lose a little bit of the emotion. But I'll still repeat them only because they're relevant.

Freshman year in school, my mom died when I was 18. Before she died, I was taking the Sociology of Death class, and that class, by chance, was just... I said, again, I want to move into my discomfort. I realized, well, I'm going to lose everything I love. Then I was compelled to write her a letter that she got only a few hours before she was killed by this drunk driver. So, this sense that there's an urgency to life that I'm not going to let slip through my fingers. That carried me at a very young age.

Then, fast forward thirty years later, my mentor had cancer, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and he had five years to live. Everyone said, "Hey, relax, it'll be fine." I'm like, "No." I went on a trip with him. I said to my wife, "I'm going away with him. We're going to spend a few weeks, and we're going to do a road trip. We'd never done that before." Then we came back, and then he died three days later.

My wife is always saying to me, "Do you have some understanding or what is it that makes you make these life decisions that seem so out of the ordinary?" I realized, no, I don't take it for granted. I never make the assumption that it's fine. I just say, "No, we're going to do this, and we're going to make the most of it." That sort of guided me, and again, that led to writing the book to show how that can become more of a way of life instead of an exception here or there.

Noah: Yeah, that's beautiful. I love that. In fact, that's a great shift into the subject I wanted to explore next because you specifically talked about the shifting relationship with mortality. In one of your chapters, you talk about this idea of being "next in line."

I was talking about when my friend Jordan passed away. That was one of those moments of realizing this could happen to me because this was essentially me, right? Another friend my age, college, all that stuff. But then there's a stage you enter where you start to realize, my dad passed away. All my friends' parents are starting to pass away. It's like, yeah, we're up next. I like "next in line," the way you framed it, and that particular concept resonated with me. Can you talk about this specific stage of life?

Andy: Yeah. I laugh when I think of what I wrote. There was a special club that you don't want to belong to, right? It's sort of there by default. I saw that when I was young, and I had my grandparents, there was always a sense there was a buffer. It's like there was a psychological sense. Of course, you could die at any moment, but there's this psychological sense—the parents were still there, so there's time. They're still alive.

Then, when both parents go, there's a sense like, "Wow, hold on. I'm the one that people look at now." It's like he's in that stage where that's the thing that he's got to think about. It sort of creeps up on you because you don't even realize. Like a fish in water, you don't realize how comfortable you are until you're there and you're like, "Wow, I'm the next one." There's no... I'm the next cohort.

So that was a realization or an experience that I see unfold in time, and going back to what you mentioned earlier, there is a degree of compassion that comes with it, a degree of humility. Because you really... in order to move through that gracefully, you need to surrender and you need to be at peace with the deterioration of your body, the deterioration of your mind. I can barely remember anyone's name anymore.

Just these things that you have to have—you need to have a large degree of self-love to make peace with all of that change and be like, "That's okay. That's where I am." So yeah, that's been, again, a big part of my own journey is just being really compassionate to myself for all of the changes that are occurring, of which it's the first time they're occurring. I've never had these experiences before. When you think your body's going to be as strong as it was when you were twenty and now you're in your mid-fifties, wow, I can't do the things I used to.

Noah: Yeah. There's a podcast episode I did called "First and Last" that I just thought of with what you're saying. It's that realization that what I'm doing is the first time, but also the last time because of the uniqueness of every moment. There's a different element with the stages, and what you're saying. Okay, this is... I'm starting to enter that phase where I forget people's names or I walk into... Wait, what was I doing?

Andy: Yeah, and that again, that sense... It can catch you off guard. It's easy to make it unsettle you. The only way that I found to slow down is to be more present to the feelings that come up when I'm in those moments and then allow them to be made peace with. If I muscle through it, it doesn't help me. That's the point. If I push through it and just say, if I'm busy enough, I'll be fine—that's not a recipe for a grounded energy.

Noah: Now, for someone listening to this and thinking, "Okay, there's this book, it's about death, like this is that big milestone that's there, inevitable at the end of my life." I love that you bring up the idea of "little deaths" in chapter eleven. Because, yes, death is the thing that's there waiting for us all, but it's the thing that can remind us that it's happening all the time. Can you talk a little bit about the idea of the little deaths?

Andy: You know, it's funny you've picked to talk about my favorite chapters, so it's funny when you're talking like... Well, I really enjoyed writing these chapters because, as you imagined, you were giving words to something that you probably had an experience of, but maybe didn't express it that way. That's how I felt. It was like, "Wow, this is a real experience, and I'm giving words to that experience."

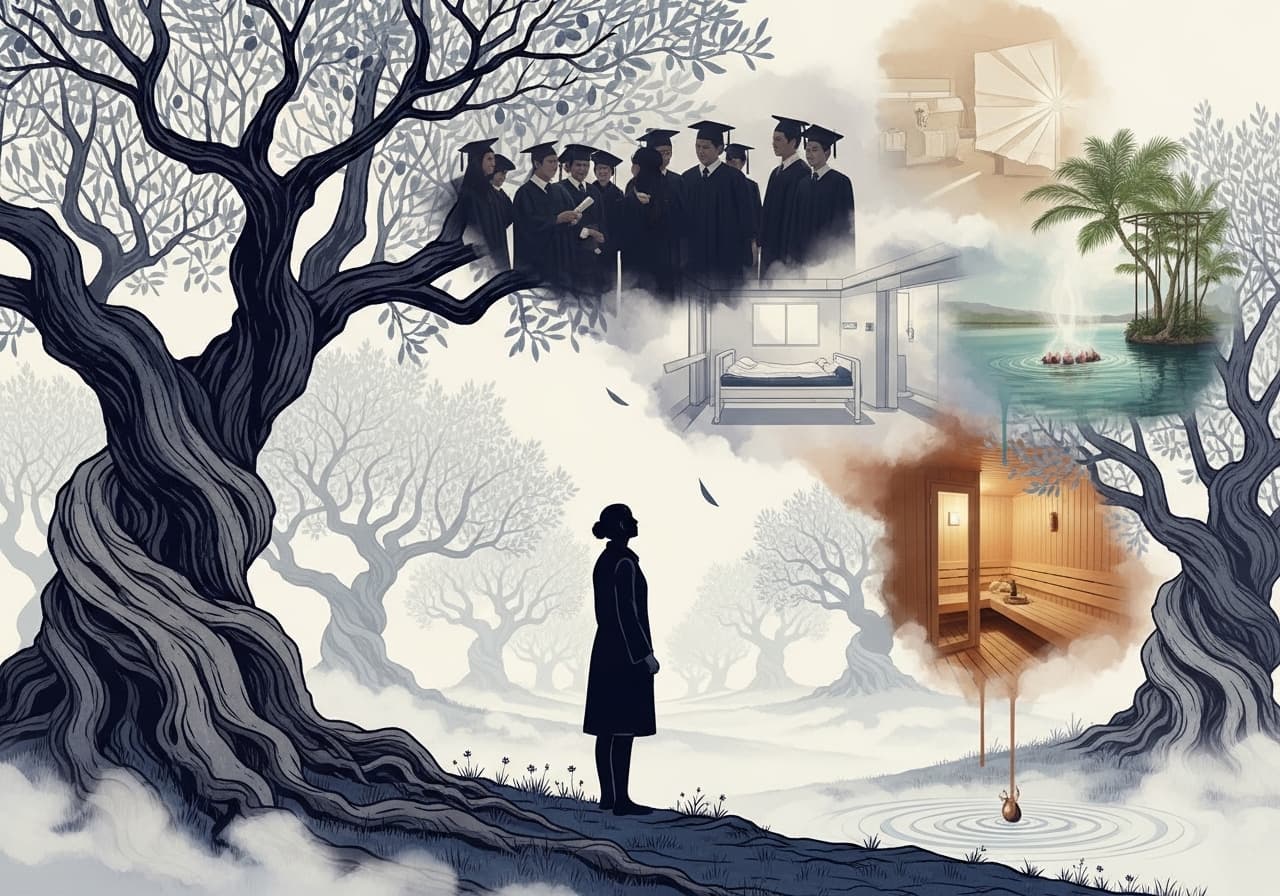

There was something that I saw in my earliest memory of it, which was graduating from high school. It was this feeling of a death, but it wasn't so big that I could experience it or emote it as if it were death because people would think that I was exaggerating or being melodramatic. So, in a way, I felt like this life that I cherished and was so meaningful for me was gone forever, like that graduation day. I remember looking around and saying, "I will not see many of these people the rest of my life. This will be the last time." There was a feeling that, "Wow, this is a loss."

So, I started to see that experience of this very deep loss resemble so much the feelings of death, but we don't express it or discuss it in that way. Then, yeah, I gave it the term "these little deaths" because in a way, it's these moments where we look at an identity, something that we've attached to, that we've given meaning to, that we then have to let go of.

It's always these moments of letting go of a person who we thought we were or something that we emotionally attached to because it gave our lives meaning. It's like losing each one by one, giving us this sense of spaciousness that we didn't even know we didn't have because we needed to be this thing, right? You know, either a successful athlete or a successful business person or a good parent, whatever the narrative is, but letting those die off in whatever shape and form is really the journey that we have the opportunity to make.

If we don't, what I think we see is that people have a really hard time transitioning because they're still attaching, the idea that they could manage it even through death, which, obviously, is impossible, but people try anyways. They just need that sense of control.

Noah: I want to go back to the little deaths. Something I really loved about the way you presented it. When I first encountered The Tibetan Book of the Dead, I was telling you about it in college. I remember a concept that it talked about—the bardo, the teaching of the bardo. The space between the transition from being alive to dying and then whatever's next. I remember for that whole part of the book, it didn't click for me. I'm not religious, so going into the realm of what happens after we die was just not interesting to me. So, I put that on the shelf. The idea of the bardo, it's like some transition state, whatever that means.

Later in life, much later in life, twenty years later or more, I was understanding more about Buddhism and the teachings. I revisited the notion of the bardo. I remember making this click: wait, if the bardo's like the crucial moment where you are aware that you're transitioning from one state to another, then it can only actually be relevant in the present moment.

The way you phrase little deaths, it's like that's it. That's what it is. The bardo is the moment that's always happening. When you realize it's that insight you had of looking around thinking, "I may never see a lot of these people ever again"—that is the bardo. And I think that's what these little deaths are. They're happening all the time, whether high school is the next milestone, or whatever's next. That's a big milestone, but it happens in the little milestones, the little moments. This interview, I don't know if we'll ever speak again. I love thinking about it. Any time it can come up in my head, I'm like, "This is the bardo between the death of a moment, what was and the birth of what will be." It's always happening. We're always in that space.

Andy: Yeah, and that is... what I find beautiful and something that hit me again. As I mentioned, as you write a book, you hit moments when you're like, "Damn, how do I deal with that?" A big gap, a big hole. And that hole was if I wrote this book when I was twenty or forty or fifty, the book would have been written totally differently. I started this and that, and so if someone were to pick it up at, say, 20 and they read the word bardo, they'd have a different attachment or meaning to it than someone who had that 40 or 50-year-old experience with death over time.

I realized I had to give a chapter to one's experience with death over time, knowing that a young reader might read it and think, "I can't really resonate with what this is, what's being shared in this moment." Similar to that, we always have meaning and that meaning changes over time. So, yeah, it's quite fascinating that you evolved your meaning on a certain word because of your life experience. I really love that.

Noah: Speaking to these little deaths real quick again, do you have any that are... What was one of the most difficult ones that you've gone through? I'm not thinking because there's big death, there are chapters of death, milestones and chapters in life, but then there are little deaths. What are some examples of some of these for you?

Andy: I love one that I'm in right now. So I left America thirty-five years ago. I left and I'm like, "I'm out of here," and I'm living my life. So, I've been traveling, and my wife got a job in New York City, and I said, "I don't know if you want this," but she really wanted it. So I went, and I didn't live there, but I spent quite a bit of time in New York for two years, and that was just recently.

Then we left, and now I happen to be living in Jakarta because she got a job here. The transition from New York to Jakarta was... In New York, everything expanded. Opportunity, recognition, money. It was like, "Wow, this feels great." That experience of uplift, I saw and I laughed at this idea, "Wow, nothing really changed except for my geography." Isn't it nice to let go of it as quickly as it came?

The joy. Now I'm in Jakarta, and it's really funny. There are very few people there. There's not the abundance, there's not this life of "We're going to change the world." It's very simple living—do we have enough to eat? We're doing great.

So I've had to sit with all of this programming that I wasn't even aware was running, of this idea of success or this idea of what I want to do in my lifetime. And so I'm having to let these ideas die, just to be fine with waking up and going to the sauna, which is absurd when you're in Jakarta and it's 100 degrees outside, and I'm in the sauna.

Then the whole thing is, "Wow, I have to let that part of my life have meaning die." Or I should spend more time helping this book find its way in the world. No, you don't have to do that. Just let it go. Then feel your system get a little bit jumpy. No, you have to let it go. It's fine, just let it go.

That revisiting these—the death of the identity that my life should have meaning—is a biggie. You know, that's so preprogrammed from a very young age, and it's reinforced in media and in the people you're talking to, the questions they ask you: "What are you doing with your life?" and "How are things going?" You thought about this. Everyone's trying to almost coach you into doing more than you're actually doing. We don't even realize the subtle conditioning that's happening in those dynamics.

So, yeah, my little death is making peace with the idea that I might spend the next years and have actually nothing to show for it. That's fine.

Noah: That's great. I think that's something all of us can identify with—the idea of ideas that we have, hopes, and recognizing they're always dying. I was just thinking, at any given time, I have probably thirty domain names that I have because it's like, "I should start a meditation app" or whatever it is. It sits there, and eventually, some I do move forward with and try something, but most don't. And I'll go back and look at the list and that domain name, what was that idea? It's not even relevant anymore, so I don't renew it.

But we have a new one that I put on there. I hadn't thought about those as little moments of these little deaths. It's the death of an idea. Because at one point, no matter how short-lived, it was full of potential.

Andy: I can very much identify with that. My mentor, who I worked with for many years, we'd come up with a new company name every three years because he's like, "Andy, it's not special enough. It's not encapsulating what we're doing." He always needed it to be something more than whatever it was, and my wife just would tease me to no end, like, another email address, another business card.

Yeah, it was this idea that it needs to be something more than what it is. In the end, you realize it's almost always about the relationship. So the name is pretty arbitrary unless it's so bad... I had a really beautiful moment. Because when I worked with him, the company name... This was when he started, it was called "Not the Carrot," right? That was the name, to force the mind to sit with the question. Then what is it? Then to see people jump to, "Well, maybe it's the stick." Realized, no, it's just not the carrot.

That name wasn't appealing enough, so of course, we went through four or five names, but he died. He was dear to me, and I had to come up with a new company name. So I took that name back, and I felt like I finally grew into the name that we started with, which is a really beautiful full circle moment for me. Yeah, it's my mentoring work.

Noah: That's neat. What does that company do?

Andy: I mentor people and do life coaching, but it crosses all spectrums. We deal with business, we deal with divorce, with children, you name it. I'm a jack of all trades in a certain way. I have friends, and we go through life together. That's my work.

Noah: Yeah, I love that. I think that's a great name. Okay, let's transition from little to big, because your book addresses the big existential questions. That chapter or a couple of them really spoke to me. The idea that we have almost this inherent need to know, and then some of the biggest existential questions, right? Is there a God? For example, the human need for answers about what happens when we die. Why? Who are we? Why are we here? Meaning, like you've talked about earlier today, I'd love to explore this a little bit, too. Something that you brought up that really resonated for me was the transition from having to have the answer to just sitting with the question. Talk about this idea of sitting with the question.

Andy: Yeah, it's funny. I go through life always a little bit frustrated with everybody all the time because, in a loving way, but it's still there. So, when someone's trying to figure something out, like, "Is there a God?" Then I see them go to a space where they detach from themselves so they're not connected to the undercurrent of what makes that question relevant to them, which would actually center them and probably bring connection between themselves and the person they're with at that moment.

So, instead, they go to a solving mindset and try to figure it out, and that's fine. There's no judgment of this is good or bad, but what goes missing in that is the idea that they are in contact, in connection with the impetus for the question to begin with. And I found that if I'm asking myself questions, then the first question I have is, "Why am I asking that question?" What is it telling me? What is that telling me about humanity as a whole? What is it telling me maybe about the weaknesses I've had or the physical state I'm in?

There's a deep richness in this self-awareness that gets deeper and deeper the more one takes the moment of this desire to look out and pushes it back in to understand oneself better. So, yeah, that's it. So, in answer to your question, when I wrote down, "Is there a God?" in that chapter, I thought, "My God, I do not want to write about this because I knew that there was going to be a potential for someone to be confronted with a belief system and saying, 'Hey, in this belief, I got that covered,' and I didn't even want to speak against that. Nor do I have any great feelings towards it.

But the thing that, as I mentioned, I would love is for people to say, "What makes that relevant for me?" And that rabbit hole goes so deep that that'll keep you occupied for a lifetime if you allow it.

Noah: Yeah. What I gathered from the way you presented that because it is... I can resonate with the idea of "I don't know if I want to present this because this isn't... I'm not trying to open a can of worms here," but what I'm trying to do is get you to transition from that, let's look externally, to let's look inwards for a moment. I gathered that from the way you presented that. That's what I gathered. It's like, "Let's think about the question for a moment." Because what that journey was like for me with those initial existential questions and then the realization that, wow, the fact that I would even care to know, that I'm the one capable of being curious and asking this is more fascinating than any answer I could get. It doesn't matter whether there is or isn't an answer. It just makes it completely about the question and about the person asking.

And I love that you're trying to take people on a journey to go inward rather than making this about whether there is or isn't. I like that. Another thing that came to me—I'm reminded of this pivotal moment in my own journey of realizing when it comes to questions and answers that when you have a question to anything, whatever the question is, it's almost like there's an itch that needs to be scratched, and one way to scratch that itch is to have an answer. And that's perfectly fine. You can have an answer. If you believe that is the correct answer, it does satisfy the itch.

The only problem with that is if another answer comes along that now puts your original answer in question, then the itch comes back. Well, is it this or is it that? Am I right? Or are they right? And the approach, the way you talk about it in the book, where we make it internal rather than external, that's to me the scenario where the question's still there, but the itch that scratches from having an answer... No, we're going to go the opposite direction and say, what if the itch goes away? The need to know minimizes, and I love that you brought this up. It's not that it's irrelevant or unimportant because for a lot of people, that is probably one of the most important questions they'll wrestle with. But it's a realization that maybe, personally, I don't need to know, and my sense of peace... Now the itch is gone. Not because I scratched it, but because I sat with it long enough that the itch went away.

I just love the overall framework for the big questions, but the little ones too. Because the truth is, we're dealing with it all the time. How long will I have this job? Will they ever end up downsizing? Will I get let go? Or relationships or whatever scenario. It's the same overall scenario of life is uncertain. You don't know what's coming down the road, and how comfortable can you be with the journey and not attach your sense of safety to the certainty of the projected future? What's at the end? What's going to happen?

Andy: Yeah, well, that's again, as I told you before, you pick out these sections of the book, which were really highlighting the impetus to write the book to begin with. The letting go of knowing is one of the hardest things. I coach and mentor a lot of people, and there'll be a lot of people that are very intelligent, MIT graduates or people that started really big businesses. I'm laughing because they will get frustrated with me because of my disinterest in knowledge. How can you be so, on one hand, in their mind wise, and on the other hand, so uneducated or not have any interest in these events? And they'll even label me a nihilist.

I have this group of friends that say, "You're just a nihilist," and I say, "No, life isn't meaningless. I'm not saying that, I'm saying I'm an existentialist. I give life the meaning that I decide to give it." I notice that over time they've become more and more attuned to what I meant because there's a nuance that's really hard to get unless you sit with your own life experience and realize that you're giving things meaning. By giving them meaning, you're actually defining what your life is. The meaning you're giving your own life. I don't know. I feel like I took your point and moved to another one now, but it felt like it was connected somehow.

Noah: No, I think it is. And that's why I highlighted that. I think something I try to emphasize in my work with the podcast or when I talk about these concepts and ideas, ultimately, it's what is the practical takeaway? How does this knowledge of a concept or an idea or whatever it is help me in my day-to-day life? I think for the topic of death, it comes to this. It's ultimately, how comfortable am I with uncertainty? Because the nature of life is uncertainty. So this contemplation, this questioning, all of this stuff, it's not academic, it's about how we actually live. It's experiential.

So I feel like this whole conversation, the deep investigation of death, of uncertainty, of knowledge—it seems to be practiced for one thing, which is the title of your chapter 27, "Waking up to what really matters." So paint us this picture. Someone who does take all this to heart and they're applying these ideas—waking up to what really matters. What does that look like? How is their Tuesday different from someone else's Tuesday?

Andy: There's this idea that there's something you go to. If you do this, you're going to have more likelihood of being ready for death. I often look at it in reverse and say, what are the conditions that if they're met, I'm more likely to be centered? If I'm more centered, I'm more likely to be like... the transition feels natural and normal.

So, I often spend a lot of time thinking about the conditions around me. There are certain people I won't spend time with, certain events I won't go to, and certain places that will make me uncentered. My wife and I have this little farm in Spain that's olives. It's got trees planted by the Moors a thousand years old that give you a sense of the permanence and the impermanence at the same time.

There's this beauty that I'm like, "Wow." I told her when I'm there, I'm most at peace to die. The transition feels so normal. The spaciousness of time, this timelessness experience. The kairos time instead of the chronos time that I write about, the Greek meanings of time. That's the area that I would say that I foster as a practice. When I'm starting to lose connection, then I'm like, "Wow. Where did I not take care of my conditions? Where did I let something go because I was attracted to an idea or something felt appealing, like this idea that maybe I'd get some recognition?" I'll chase after that and only realize, "Wow, I lost everything that made life meaningful and connected and special."

So, I'm very cautious about what I bring into my life so that I don't get drawn into or away from just being centered and present.

Noah: Yeah, I love that, and you framed it like I'm ready to experience death at any given moment. When I think again back to this concept of the bardo, that space between... thinking of it as the transition between life and death. And you think of it moment to moment. How could I be to truly be ready for death? That death means I'm ready for the birth of the next moment. Or in the phrase that I'm ready for death, what that really means to me is I'm ready to be alive. I'm ready to truly live.

And I think that's the connection that we have in our society without realizing that the resistance to the thought of death, to talking about it, thinking about it, feeling what comes up when you think about it, ultimately is a resistance to being truly alive. Because they're inseparable, right? One gives rise to the other. But that for me clicks more when I bring it down to the timeline of moment to moment—the little deaths. And it's like, yeah, if I could just apply that and practice it in the day-to-day little death experiences, and I become more comfortable with the idea of embracing the present moment as the passing of a previous moment and the next moment—I could extend that to the bigger existential one, the idea that it's no different at the end of this life, there's death.

I always find this interesting. For most people, we dread what's to come, but never do we think about it with existential dread of everything I missed before I was born.

Andy: I think about that a lot. That again was a fear as a child of the thing that you just mentioned. I didn't exist for billions of years, and I won't exist for billions more years. Both sides got me very uncomfortable, and yeah, wow. Well, that was it. It came from an early age, for sure.

Noah: Interesting. I think most people don't think about the other end of that timeline. That's interesting that you... I think that goes... You think deeply about the topic.

Well, so let's bring this home with practicality again. I love that you mentioned this idea of sitting with the question of "if today were my last day." I think this is a very powerful practice. I want to acknowledge here that, in a very literal way, I know that if today were my last day, I probably wouldn't be doing this interview. I wouldn't be thinking of work today, right? I would spend time with my family doing the little things, just... So I get that if I thought that every day, then I wouldn't be able to pay the bills. There'd be a lot that I wouldn't be able to do.

So keeping that in mind, I recognize that, but the heart of the matter with the question is, if it really were my last day, what things would matter that I didn't realize mattered? Or what things are backwards, right? What things that I think are a big deal, I would realize maybe that's not a big deal. That's how it is for me when I think about that. But let's talk about this a little. This perspective of "if today were my last day." Could you explain that practice a little bit?

Andy: It's funny, I experienced it a little differently than the way you just... I was listening to you, and interestingly, I thought, wow, the way that you would articulate it resonates differently than how I would articulate it. Which I thought was quite curious. Everything you said made sense. I thought to myself, maybe I have a warped way of looking at this, but I'd love to dissect it and share.

I have always felt like the saying, "If it's my last day, I'm going to spend it with my wife, right?" That isn't the way I've kind of framed it in my mind. I've always framed it in the sense that, "Am I present to the moments I'm in?" If I'm present to the moments I'm in, then everything feels grounded and centered. In this sense of the fullness of being, if I squash the moment, if the moment you and I are in it right now... I see myself flip into a state, "Okay, I'm going to start to explain stuff to you, and I'm going to rapidly speak, raise my voice, and I'm going to start to lose the connection and move into that kind of space."

That's when I'm like, "Wow, I just lost that five, ten, twenty, thirty minutes." I was so unconscious of my reactive behavior that I reduced it to more everyday speech that I'm not here now. I'm not being with you, and that's what I cherish.

I was really unwell a month ago, really not well—one of the lowest moments in my life. Even a bit fearful because... Then I had a podcast with you. It was one of those bigger podcasts. I can't even remember the name now, but it was one of them, and I wasn't centered. I wasn't present. I was anxious because I could feel more things coming into my consciousness.

Then I watched that podcast back and I cried because I saw that guy, me, who couldn't be present to his discomfort at that moment. And it was just... I could cry again now feeling... I was so sad for that guy. Wow. You really were not in a good place. I needed to see it from a centered place to see how uncentered I was then. And that's my last days. The last days, you and I having this talk, if I had a heart attack and felt like I spent a beautiful time with Noah, that was special. That's good, you know? That's the feeling.

Noah: Yeah, I love that. So two thoughts come to mind as you frame this way. One was... I think it was Milarepa or Tilopa, one of the Tibetan poets of yesteryear, had a quote that said, "My religion is to live and die without regrets." I processed that over the years, what does that mean? What does it mean to me? It's what you just described. I'm trying to live my last day, any day, as if it were my last day where I don't have the regret that I should have done it differently. It's like I'm just... the way that it unfolds.

And I think that's hard to do for a lot of us, especially if you're constantly weighing what is with what should be or what could be. We play that mental game. That's one thought that comes to mind, and then the second one is an exploration that I think comes from Alan Watts, where he talks about this idea that imagine you are God and you are all-powerful and you can manipulate reality in any way you want.

So you live out and you have eternity. So you live out all these multiple lives—in this one, I'm a billionaire, and in this one, I'm whatever. Across virtually eternity, in every scenario that you can imagine. At some point, you'd say, "Well, now I'm going to do something really surprising. I'm just going to wake up and not even know who I am." Wake up today as me, right? This is the life I'm living.

That came to mind with what you were just presenting again—that idea of the last day. What if it's perfectly okay to just... it's what it is. It's what this is because, again, the idea of uncertainty. I don't know. What if you and I really are God, and this is the day we're just waking up, living an ordinary life of whatever your day is today? That brings to me that connects with what you're trying to imply here. This idea of, what if that's the practice? Is that this is your day, this is your moment. How are you living it? How are you showing up for the moment that you happen to find yourself in? Now, knowing that it may be pleasant or unpleasant, it doesn't mean it's good or bad.

Because you talk about this with that story of the horse, and who's to say what is good or bad, which I love because we're always doing that. But it is waking up and thinking, "Yeah, it's unpleasant. I'm dealing with the flat tire right now, but it doesn't mean it's bad, and this is my moment. How am I going to show up for this moment?" That's what you're saying, right? That's the practice?

Andy: How am I going to show up for this moment, you know? Even if I'm shouting out of frustration, I'm always laughing a moment later. It's almost like the full expression of life without the cumbersome idea that this is bad. It's like, whatever. We have the natural expression of this is not what I wanted or expected, but that doesn't mean that I now need to make it anything bad.

I had this funny moment, as I told you before, I'm now in Jakarta, and I don't go out that much. It's hot, it's polluted, but I'm like, "What am I going to do? I'm going to walk. I'm going to go on public transit. I'm going to experience this place." Then I ended up in some random place, very uninteresting, North Jakarta. A lot of industry, a lot of pollution, but there happens to be an amusement park. So I'm like, "What am I walking through?" I'm in an amusement park, just the most random of experiences.

I was sitting with this, like, "How does it feel to be here, experiencing this, seeing all these people looking at me like, what is this guy?" This guy seems crazy because I was the only foreigner in this place. It wasn't necessarily anything. It was a replica of Disneyland, but on a much lower scale. I mean, it was wonderful. I cherish that day as a moment in time to discover and explore and see myself react to the environment I was in, see the judgments come up and the humor that I had to my own judgments of things.

They had "It's a Small World." It was a replica "It's a Small World," but done with 80% of the animatronics broken, and the paint was peeling off, and the boat wouldn't go forward, so I had to pull it forward. It was just a wonderful, absurd mess that was so wonderful to have experienced.

Noah: I love that you said, "I was in this moment." At the end of the day, it's all we have. We're in this moment. The only moment we've ever had that we will ever have is this moment. What is one simple thing someone could do today to start using this awareness of death as a tool for better living?

Andy: Well, there's one tool that I slavishly go to. I wrote a book called The Wounded Healer. The practice that I use so often and everyone knows me for is, I say, "The thing that I'm most fearful of, most anxious of, most angry about, most embarrassed about"—it doesn't matter. Any emotion on the spectrum. I state the thing, and it's okay. I'm going to die. Maybe there is no eternal nonexistence. It's okay, and then I might even move it up a level, and it's fine—really give it a full body.

What I've seen is we're not doing an affirmation here. We're almost giving our entire system the opportunity to ground whatever is in the back impacting us all the time, impacting us whether we like it or not. So the only way to resolve it is through it. You don't manage it, you don't think, "Maybe there is... If I say and tell a story, I won't feel as bad about it, right?" Yeah, coping mechanisms. No coping. Just take the raw thing that's the most difficult thing to accept and just make total peace with it. I'm going to die, and this might be the only time I have is in this consciousness. That's fine. It's great. It's okay.

Then that system of relaxation means, what do you think? Of course, I'm going to be present again because I'm only not present when I'm resisting a feeling that I don't want to feel and coping with it. That's not present. That's a coping mechanism, hoping that the subject doesn't come up or... So, this real, grounded... Let me make full peace with every single thought in my head, whatever it is, however hard it might be, because if I don't make peace with it, it's still defining my life in ways that I have no control over.

So that's the one thing that I spend a lot of my life just going through as a quiet acceptance over and over again. It's okay. There's a beauty to it that I've discovered, and there's a beauty in the things that are unresolved because you're like, "Wow, that's there." "Wow, that led to the book." This book was like, "Wow, that's still there." That's not... I can't wish that went away too quickly, so that lent itself again to write the book.

Noah: I love that. With that, it's okay. It applies to someone who will sit with it and say, "No, I'm really uncomfortable that I'm trying to sit with this, and I'm not okay. I'm still afraid of death," but that "it's okay" applies to that too. It's like, it's okay.

Andy: Exactly. It goes to every single thing. I'm not okay with saying, "It's okay," and that's okay. I mean, it never ends, actually, because I've seen people. I laugh, and they're like, "But I don't feel comfortable with that," and I'm like, "Yeah, that's okay." You can be okay with that not being... It can take you as deep as you want to go, or as superficial as you want to go.

Noah: Yeah. And what's cool about that as a practice is, like you said, it works for anyone. The person who is experiencing the existential angst and the one who isn't, who's like, "Yeah, I'm okay." By just getting into that framework of whatever, how am I showing up for the moment? Whether the moment is a moment filled with panic at 3 AM because I'm like, "No..." Is it okay? That's what I'm feeling. It applies in all the scenarios. I love that.

I do want to say that this has been a really profound conversation. And like I mentioned before, I really enjoyed your book. You've taken something that most people tend to want to avoid and shown how it can be our greatest teacher. I hope that's what people will take from this interview with you—that the idea of maybe I'm willing to pick up that book on a topic that I'm uncomfortable with because maybe it could be my greatest teacher.

So let's talk real quick as far as telling our listeners—where can they find your book, Dying to Live? Where can they connect with you and your work?

Andy: You know, Barnes & Noble and Amazon and Kindle and it's audiobook, so it's basically everywhere that you can get a book online. And that was the first question you had. A second question. What was that? That's where you can get the book. About me—AndyChaleff.com. It's funny, most people who write have a funnel or a pipeline, saying, "Hey, I've got things, I'm going to upgrade you." I don't have any of that. I actually... It's almost like I write from a deep passion of connection, and I just want people to have that experience.

I write my own blog on occasion, and I write for Psychology Today, and I have an article in Esquire that came out, so I'm getting exposure through my writing. But when it comes to living and having my quiet time, going back to what we said, I really don't tend to want to do big courses or big trainings or things. It's a lot of energy. I'm an empath. I have a lot of that empathic kind of energy. So I'm picking up the energy of the people around me, and it can be exhausting if you're in big groups and managing all the emotions that you feel coming into your system.

So you can contact me through my website, and I create what I think is fun and interesting content. So it is worth a look. The website itself is quite fun. It's a celebration of how I like to show up in the world. It's not... Most people that go there are like, "Who is this guy?" and it doesn't seem like he cares about how he's positioning himself. I tell my whole life story. I graphically designed my childhood trauma and everything. It's all out there on page one, you know?

Noah: Nice. Well, I appreciate you taking the time. I know it's late for you where you are. This has been a wonderful conversation.

[Note to readers: At this point in the interview, Andy's connection briefly dropped—a fitting reminder of the impermanence we'd been discussing throughout our conversation.]

For more information about Andy Chaleff and his work:

- Website: AndyChaleff.com

- Book: Dying to Live (available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and all major retailers)

About the Secular Buddhism Podcast: Visit EightfoldPath.com for more episodes and resources on Buddhist philosophy and mindful living.